Once again, Thomas Arnett at the Christensen Institute has used his keen insights about disruptive innovation to shed light on the specific forces that keep public education tied to conventional models that don’t work. His keen insights and crisp, action-focused analyses inspired me to write another “yes and” response.

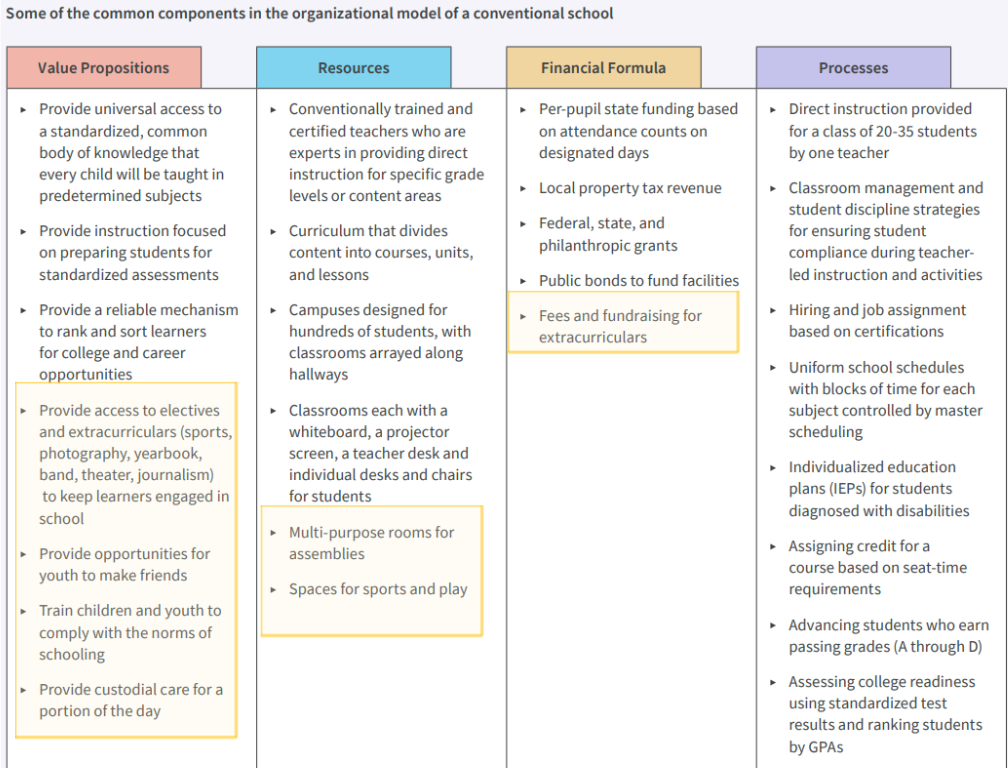

Arnett has condensed his reflections on whether and how it was possible to create equitable learner-centered ecosystems into a tight 40-page report produced in partnership with Education Reimagined. K-12 Value Networks: The Hidden Forces that Help or Hinder Learner-Centered Education is well worth the read. It’s got everything big picture thinkers (like me) crave – a mercifully brief recap of the evidence that the U.S. education system isn’t working; a refreshingly different take on why the system’s organizational model makes it almost impossible for it to self-correct; five different, but equally compelling, examples of innovations that have worked but not scaled, accompanied by wonderful one-page summary charts for easy comparison; and a breakdown of the key influencers in learner-centered value networks (the individuals, organizations, institutions, and regulations the system interfaces with to establish and maintain its model). So much to work with! Look, for example, at Arnett’ summary of some of the common components in the organizational model of a conventional school.

This chart makes it frighteningly clear the extent to which the resources, financial formula, and processes that define conventional schooling align with the top three value propositions (in column 1) to the point that they squeeze out the bottom four value propositions, which in their lack of robustness reflect the system’s lack of commitment to anything close to “whole child education.” I have color-coded the chart to underscore how the majority of resources, financial formulas, and processes align with the focus on the “assembly line” approach to schooling. As you look at the highlighted bullets, note that the there are no staffing resources associated with the non-academic value propositions, just space accommodations; no dedicated financing (only fundraising and parental fees); and no processes associated with ensuring students have access to or receive credit for growth in non-academic areas.

Arnett notes that organizational models are not static. Schools regularly update curriculum, revise professional development programs, or introduce new technologies that streamline scheduling and record keeping. Changes like these are easy to implement because they enhance rather than challenge value propositions or endanger the financial formula. “Other types of innovations – such as competency-based learning, flexible learning pathways – prove perennially difficult for established schools to adopt because they don’t fit well with the capabilities of the conventional model or the priorities of its value network.” (p.12)

An organization’s value network, Arnett explains, is the collection of external entities that it interfaces with to establish and maintain its organizational model. “The value network shapes the organization’s behavior by providing it access to resources, regulating and interfacing with its processes, providing it sources of revenue, and being the source of demand for its value propositions.” (p.12) The value network of a public school often includes local, state, and federal education agencies; learners and their families; employee unions; voters and taxpayers; the postsecondary education system; community organizations; vendors; teacher preparation pipelines; and philanthropic donors.” (p.10)

Arnett posits that learner-centered environments that offer a more holistic approach to public education are “few and far between” because “even when education leaders recognize the need for a new model of education, learner-centered reform efforts in conventional schools consistently get nullified by the powerful, yet underappreciated, collective force of a schools’ value network. His conclusion is spot on:

“Different value networks embody different priorities, and new models of learner-centered education can only take root successfully within value networks that align with their distinctive priorities.”

He and others looking to reinvent public education, however, may be underestimating the power and potential of forces hidden in plain sight that stem from equally old ideas brought to the U.S. from the U.K. in the late 1800s. Consider this summary of the settlement house movement from the Social Welfare History Project:

“From the outset, there was a remarkable lack of orthodoxy in the settlement movement; the settlement idea remained a very general one, assuming different forms in response to different conditions, each settlement drawing its specific methods and aims from the needs of its community. Flexibility was the key. The basic idea, however, was constant: a settlement was to be an outpost of culture and learning, as well as a community center; a place where the men, women, and children of slum districts could come for education, recreation, or advice, and a meeting place for local organizations. It was usually run by two or three residents, under the supervision of a head worker. They would live at the settlement and involve themselves as fully as possible in the life of the neighborhood, studying the nature and causes of its problems, and developing rapport with community leaders—teachers and clergy, police, politicians, labor and business groups—in order to facilitate the development of its independent life and culture. The internal structure of a settlement consisted mainly of the various clubs, civic organizations, and cultural and recreational activities—such as lectures, classes, and child-care—that convened under its roof.”

The settlement house movement planted the seeds that became social work that still undergird the basic value propositions of community work and youth work. Local organizational models exist in YMCA’s, Urban Leagues, Neighborhood Houses. Local systems that bind together separate organizations into the kind of cohesive, modular ecosystems Arnett wrote about in his earlier commentaries exist. The strongest of these have been fueled by federal funding to support the expansion of afterschool programming for disadvantaged students.

These organizations and networks have a commitment to holistic learning and development. Their value propositions come much closer to those embraced in learner-centered education. Few, if any, have assumed responsibility for the main value propositions that define public school – universal access to specified knowledge, standardized assessments of knowledge acquisition, and mechanisms to rank and sort. But this is what makes understanding their operational models and value networks so useful. We need to complement Arnett’s chart and local examples with ones that can show commonalities in how resources, financial formulas, and processes get defined in and supported by value networks that are fundamentally more aligned with learner-centered education than those associated with the conventional education system.

Compiling examples and extracting common lessons from local leaders across the country who have built sustainable learner-centered systems not designed to deliver academic credits is a critical next step. Our ability to give school leaders the capacity, motivation, and opportunities needed to co-design equitable, publicly funded learning and development systems requires market research investments in the “community learning system” co-designers. Experience shows that bringing these two systems to the table, even when both are well on the path towards creating learner-centered experiences, is very difficult.

Our ability to give school leaders the capacity, motivation, and opportunities needed to co-design equitable, publicly funded learning and development systems requires market research investments in the “community learning system” co-designers.

Case in Point. Providence, Rhode Island. Providence is the home base of The Met, one of the oldest and most highly acclaimed models of learner-centered education (see Arnett’s profile on page 19). Providence is also the home of the Providence After School Alliance (PASA), which as one of the oldest and most highly acclaimed entities of its kind, shares a status on par with The Met but within a different constellation – the growing network out-of-school time (OST) intermediaries that are a part of the Every Hour Counts network.

Over the last 18 years, PASA has built a nationally recognized model to provide programs` and services to young people. They provide logistical support, quality programs, a team of committed providers, and resources to support more than 50 community organizations in serving more than 2000 middle school and high school students each year – primarily out-of-school but in some cases during the school day as well. PASA’s AfterZone (middle school programs) and Hub (high school programs) provide access to STEM, arts, physical activity, and meaningful relationships with adults and peers. Additionally, at the high school level they facilitate a network of providers to offer credit bearing OST courses. (For comparison purposes, the Met has a network of six small high schools in Providence and Newport, Rhode Island, that serves approximately the same number of students.)

PASA is a trusted partner in the community and has demonstrated its effectiveness at providing learning and development opportunities that youth and families attend and fund voluntarily. Beyond its core programming, it has modeled its ability to contribute to students’ academic progress and career success. One such example was a pilot partnership in which PASA’s STEM partners from the afterschool space were brought into the school day to provide light touch programming that complemented the teachers’ curricular units. Another is PASA’s robust badging system. Students earn badges by participating in courses through Rhode Island’s All Course Network. Badges can be shared on job and college applications and resumes. These badges are also tied to priority placement in the City of Providence’s summer jobs program.

Ann Durham, PASA’s executive director, notes that in many cases organizations like PASA (and their community partners) are more adept at providing new types of learning experiences that are more aligned and integrated not only with families’ preferences but also with 21st century workforce demands. In many ways, she says, schools should see out-of-school time programming and infrastructure as examples to learn from. Realistically, however, she doesn’t expect this to happen without intentional leadership and funding from the school system or other stable public sources. Even in a state like Rhode Island where seat time is not a driving factor, school systems have not fully embraced the payoffs of supporting learning that happens in the community.

For example, in Rhode Island very little ESSER & ARPA funding flowed into the out-of-school time community, even though passing through funding to expanded learning providers was both allowed and encouraged in the federal guidelines. Durham shared, “The ESSER money did not go to the out-of-school time community. The ARPA money did not go to the out-of-school time community. There are some discrete examples of districts that use their extra funds to expand afterschool and summer within their districts. But as a whole Rhode Island did not invest in this.”

This funding uncertainty came at a time when families and students that had lost trust in the school system were looking to the out-of-school time community to meet their increased needs and looking to PASA for additional coordination supports, and when coordination with schools was more needed than ever.

“There’s not been the type of statewide and district level strong support and support and guidance that other states enacted which would enable the financial decision-makers to better understand how they could direct the funds in this way. I don’t expect a principal to know how to partner with a community organization or to know what community organizations might best address their students’ interests and needs. I don’t expect a principal to know that they can use their…funding to pay a community organization to do the work,” Durham said.

Organizations like PASA stand ready to play these roles for school leaders across the country. Some are making headway. We need to study and engage them not just because they increase the effectiveness, sustainability, and reach of the programs in their networks and act as an efficient negotiating partner with schools. We also need to study and engage them because they have decades of experience developing the infrastructure needed to run alternative operating models that have features we can learn from, leverage and adapt.

Adaptation will be needed. The connections are not obvious, even in communities like Providence where there are established learning system innovators that represent both worlds.

Supporting partnerships with community organizations is the Met’s raison d’etre. And engaging high school students is one of PASA’s passions. But the two Providence-based intermediaries do not work together closely. This is not uncommon. It is understandable. But it is also unfortunate.

Both intermediaries are committed to providing students with powerful, interest-driven learning experiences that connect them with a broader group of people and places in their community. But while there is some overlap (e.g., outdoor experiential education sites), the organizations that are staffed and open to provide place-based afterschool and summer learning opportunities (e.g., youth organizations, libraries, community recreation centers) are not consistently the organizations that are staffed and available to offer internships, job-shadowing, career mentors, and project-based field learning opportunities during the school day.

This difference in the organizational partners recruited from the community has masked the commonalities in operational processes and financial models needed to support equitable, community-based learning ecosystems designed to ensure all young people build the competencies, connections, and confidence needed to thrive. To renew our public education mandate requires rethinking what is mandatory – the restrictions on what, where, when, how, with whom, and in what order learning experiences are accessed.

As Ann put it so clearly, what needs to happen next is schools “have to stop bifurcating what we do and focus on better coordination of what exists.”

2 Comments

Thanks for taking the time to comment Jim. We’ll do our best to continue to feature examples like PASA and to follow Tom Arnett’s wise strategy of looking for the commonalities across them that can inform our thinking.

Karen, Thank you so much for sharing this “yes and” response to the very important Christensen Institute white paper. I really appreciated learning about PASA and can clearly see the benefit of learning from these thriving, publicly funded and pre-existing organizations as we work to move forward with a community based ecosystem model option for “schooling”. I hope we can learn more from PASA and the other out-of-school organizations that are already managing networks of learning. All the Best, Jim Bailey