I had a chance to sit down with Stephanie Malia Krauss to learn more about Whole Child, Whole Life: 10 Ways to Help Kids Live, Learn, and Thrive. As long-time collaborators with Stephanie, Karen, Merita and I are hopeful that you’ll be as excited about this new book as we are. In this Q&A interview we explore:

- Stephanie’s journey to writing Whole Child, Whole Life and her decision (about which I’ve previously shared my excitement) to write this book for all adults that refreshes and synthesizes the research on what we know about young people and makes it accessible to everyone who cares for kids

- Key sections of the book and the scientifically-grounded methods you can use

Stephanie Malia Krauss is an educator, social worker, and leading voice on what young people need to thrive in a rapidly changing world. Through her consulting shop, First Quarter Strategies, Stephanie works with US-based networks, coalitions, philanthropies, nonprofits, government organizations, schools, and community groups. She is the author of Whole Child, Whole Life: 10 Ways to Help Kids Live, Learn, and Thrive and Making It: What Today’s Kids Need for Tomorrow’s World. Stephanie’s work and writing have been featured on NPR, PBS, Insider, and more. Stephanie is a senior fellow with the CERES Institute for Children & Youth at Boston University and Education Northwest. To learn more about Stephanie and sign up for her newsletter, visit www.stephaniemaliakrauss.com.

Part One

Creating Timeless Wellness

Katherine Plog Martinez

The KP Catalysts team are huge fans of your work and Making It. Can you tell us what brought you from the release of Making It to the decision to share Whole Child, Whole Life with the world?

Stephanie

Malia Krauss

I think of Whole Child, Whole Life and Making It as close cousins or companions. Making It was written after my first decade–ish of working in national work as my, I call it, love letter back to the frontlines. Making It was this book about what young people really need to be ready for a world that is unjust and unfair, and really need to be ready for adulthood and a changing future. And then the book came out in the middle of the pandemic, and we were all at home. I was doing this pandemic book tour from the basement with the microphone.

Whenever I would talk to a group of teachers or youth workers or counselors or parents, I would give all the information on how the world was changing and what our kids would need for the future and somebody would raise their virtual hand and say, “I need to know this information. But I’m also so worried that my kid is going to give up or burnout before they get there. Our kids do need to be ready. But I am really worried that our kids are not well. What does wellness require?”

So for me, when we think about what it takes for young people to thrive, they have to be ready for a hard challenging world and equipped for what that actually requires. But they also have to be well in the world. When I think about the kids in my life, I want them to have a good life. I want them to enjoy life. I want them to live lives that they love. That was the hope of Whole Child, Whole Life. Where Making It was a very timely picture of the world as it is right now – What is it going to take for young people to make it in adulthood? make it in college? make it in work? And what does that mean that we have to be doing? Whole Child, Whole Life is about what do they need to be well? Their well-being. And what do they need to be well across their lives? Their well-becoming. I think together then you have this picture of what it takes to thrive.

The power for me, particularly as a mom who’s in those trenches right now, of Whole Child, Whole Life is that the information is much more timeless than Making It. So Making It will hold as long as we’re having the kinds of disruptions and volatility that we’re having right now. But what I found when I was writing Whole Child, Whole Life is that the things that make us well – the things that enable us to love our lives – they’re totally timeless, and they cut across any context in any culture. It’s just a matter then of how you set up the conditions for it to happen given who a kid is and what’s happening in their life and what system or setting there in.

I love that you brought up your perspective as a mom. We’ve talked a lot about the intersection of the parent hat and the professional hat, but I think one of the things I’m most excited about with Whole Child, Whole Life is that you opted to write this book for any adult who cares about children, rather than for those in a professional role that works with young people. And I’m wondering if you can tell us a little bit about why you made that decision. Why a book for any adults, not just for educators or counselors?

Yes, that was such a deliberate decision. Ultimately, it’s anybody who cares for kids. Anybody. No matter who or what capacity. It comes out of that space of recognizing that when a young person is with you, they are in your care. There’s going to be learning that’s happening. There’s going to be growing and development that’s happening. And potentially there’s going to be conflict and hardship and challenge that’s happening.

So whether you are a ninja coach, a camp counselor, a teacher, a parent, a grandparent, a neighbor who’s watching the kid for a couple of hours, a faith leader, from the perspective of a child, you are the adult responsible for them, for whatever might happen in that period of time. And in this particular moment – so here’s where we move from being timeless to timely – there is so much division, dissension, disruption between conversations happening, or not happening, among the adults who are caring for the same child. But the concerns are shared. One of the things I wanted in writing Whole Child, Whole Life was that, in the life of the child, any single adult who has some part of responsibility for that child’s learning, development, and time could read the same thing. Because, fundamentally, the book is about what does a child need now and what do they need next?

I think even with professionals, we take these kids and then we call them, students, clients, participants, campers, athletes. The other day I was talking about this and I realized how it would feel for Harrison, my rising fifth grader, if his teacher, Mr. Macklin – who was his fourth grade teacher and now is also his Y camp director – were to come up to him and Harrison were to say, “Mr. Backlund, what did you do this weekend?” And he were to respond, “Harrison, you’re just my student. I don’t talk about that with students.” From Harrison’s perspective – you can feel that in your gut – it would crush him. Because for Harrison this is the adult who he looks to – who was in charge of him from 8am in the morning until 3:30pm, who then did coding camp and sometimes had him until 6pm, and who takes care of him in the summer. This is an adult who is caring for him, who is a very big person in his life.

So the other part of this, a little bit maybe more subversive, was that we have to reclaim the art and science of raising and working with kids and see that it is the art and science of child care. How do we care for them? And how do we help prepare them? And what’s the science of that and how are we all cross trained, regardless of role or title, in every aspect of the fundamentals of how you care for kids, and how you prepare kids?

Part Two

A Child's Portrait

That’s great. I’m thinking as I’m listening to you: You’ve talked about wellness. You’ve talked about thriving. You’ve talked about readiness. And I know that like us at KP Catalysts, you care a lot about words and what they mean. So, let’s talk about the title of the book. I think “whole child” is a phrase that gets used now a lot. And people use it in lots of different ways in education and in broader society. And I’m wondering how you define “whole child” and why the addition of “whole life”?

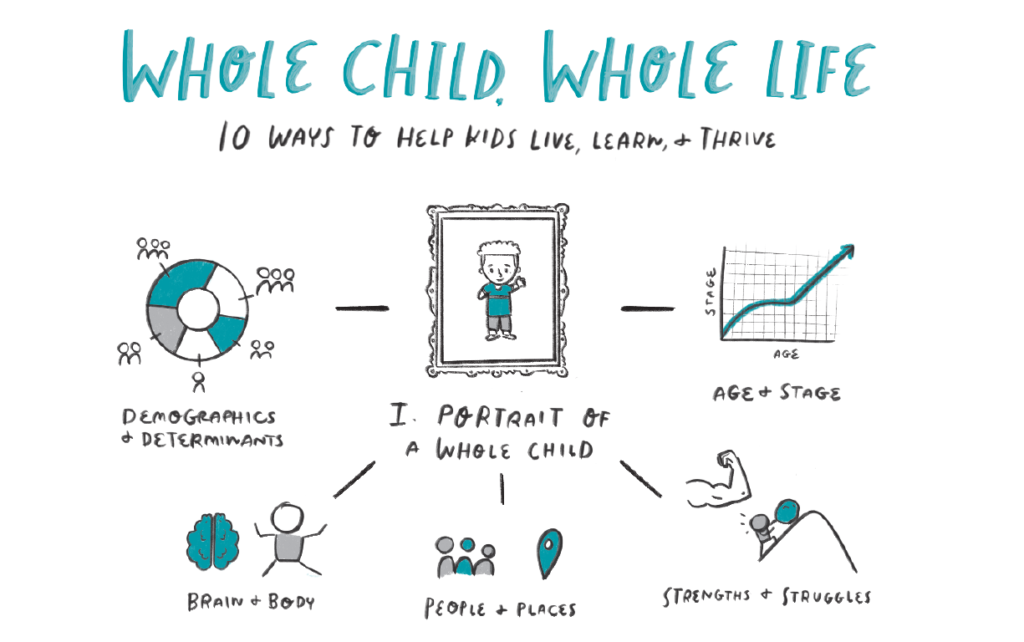

I wanted to really look at if we say we care about the whole child, what actually are all of the components of what that includes? And how do we begin to inform ourselves on who that kid is fully, and who that kid is in context. So very often, when we’re talking about the whole child perspective in schools, we’re only talking about what is happening internally with that young person inside of the school setting as a learner. Or if we talk about whole child approaches broadly, that can sometimes become a catchphrase for support services or services outside of the school, and so we use this language as a way to kind of cloak or umbrella over the things that don’t have good categorization.

What I wanted to do in the first part of the book was actually walk through this really systematically. How do we begin to know the sort of crudest outline of who a kid is and then fill out that full high definition portrait of all of the pieces that allow you to look and be like, “Oh, I get it. I get who this kid is. I get what their world is like. I get how the world treats them – how they experience the world.”

That part of the book and that framework of understanding who a whole child is breaks into five components:

The first is around demographics and determinants. Basically, what happens based on how a kid looks and how a kid lives, and what does that do in terms of how they’re treated? What does that do in terms of the resources and opportunities they have? So this idea of treatment and resources and opportunities, on the one hand, is a personal reflection for us as adults of how do we judge and change our behavior and actions towards kids based on what we perceive because of how a kid looks and how they’re living. But it’s also getting ourselves as educated as possible on what it means for a young person to move through the world, to move through school, to move through systems – based on whatever their particular profile is of all the various kinds of identities of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality – but also through the historic moment in time, the political moment in time, the social moment in time, the community feel, the environmental feel.

Once you understand how life is going to work, and how a kid is going to be treated based on how they look and how they live, it’s then what’s going on with them developmentally – age and stage – and there’s a connection there for sure. It’s also understanding where they’re at socially, emotionally, cognitively, and how those can be very different. If we talk about it in a pandemic moment – our kids growing up slow and fast – we’ve got to take stock developmentally. In the book, I walk through literally all the developmental milestones and how they kind of adjust based on who a kid is. Some young people, based on their profile of determinants and demographics, are treated like adults way earlier than they actually are adults. And what does that do, for example?

Then we move over to physical health – brain and body – which I think many of us are not well trained in and are often confronted with if our kids get sick or if there’s a chronic condition. And that chapter, that’s where I think I actually learned the most writing it. We talked about imbalances and inflammation and injuries and also how the body needs movement and sleep and those other pieces. Those are really kind of the internal pieces of building out the picture of who the kid is.

And then you have to situate it in context. So if you think of a portrait, you think about that hanging picture, and what are the background details. The part of a whole child perspective often missed is people and places, mapping a kid’s world. Having them map who are all the people in your life and what’s it like when you go to the gym and what’s it like when you go to the Y and you go to school and you go to grandma’s house? Or how would you create your world and how do I get to know that world? This is as important for a parent as it is for a teacher or a counselor because it’s about entering in and seeing the world from the child’s perspective. And recognizing how it’s viewed from that perspective.

Then the last piece of that portrait I think about is the fine details. This is where I talked about coming into high definition. It’s about a kid’s strengths and struggles, their worries, their characteristics. It‘s the piece of when you walk in and you’re like, “That’s Abigail,” or “Something’s wrong with Abigail,” or “Oh my god, something amazing happened to Abigail,” or the same for Justice. (Interviewer’s note: Abigail is my oldest daughter. Justice is Stephanie’s oldest son.) It’s when we get to a point of knowing a child that we know in a moment when something is wonderful or something is terrible or something is off. We just know what makes them who they are and what I say in that section – with a mom’s heart – is I want adults who really know my kids. I want adults who go so much farther than that initial crude profile who really know them.

And that’s really kind of the call. That we would progress in whatever capacity we’re caring for kids. It’s an evolving practice because kids are always changing and growing. We have to keep getting to know them. They’re changing and evolving at a rapid rate. So we have to keep practice and keep inquiry as kind of a cornerstone.

Part Three

The Long and Wide of Life

From there, you take the readers through 10 Whole Life Practices. Tell us about those.

The whole life practices, as I think about them, are the whole life being the long and the wide of life. So these are practices that kids need adults doing for them while they’re growing up in the wide of life – any of the spaces and places where they’re spending time. This is what sets up the conditions for them to thrive, for them to be ready, and for them to be well.

But the long of life, that’s well-being. Do I get to experience well-being everywhere I go and around anyone I’m with? And if not, what does that mean? And how do I get the supports and services I need?

The long of life is recognizing these practices adults are doing for us, if I’m a kid. I need an adult to meet my basic needs, because I’m a kid. I need an adult to help build community and belonging, because I’m a kid. And I’m going to benefit from the nourishment of the adult setting up the conditions where there is good community and where I belong, and there’s healthy relationships and my basic needs are met. But the idea is that those practices would become internalized and that eventually they will become self-care practices. So there is a perpetuity to these practices that is absolutely crucial. And that’s what I was really after, because the science is very clear that if kids have the right resources and opportunities, they have the possibility of living to be 100 years or longer. That’s an awfully long life. Now of course, we know from an equity perspective if they don’t have the right resources and opportunities, if they’re exposed to unsafe things, that prospect comes down. But with the right resources and opportunities, science has just made it possible for us to stay alive longer.

We have to set up these foundational things that are going to endure potentially for 100 years or more. What kids experience modeled – and what they experience for themselves – then needs to be internalized so they can take it with them throughout adulthood. For example, I need people to be meeting my kids’ basic needs while they’re kids in school or at camp. But when my child leaves this house as an adult, I need him to know how to meet his basic needs. I need him to know how to prioritize his mental health. I need him to know which are healthy relationships or which aren’t.

So I think there are these 10 practices that have emerged from the science and research that support the long and the wide of life, that support well-being and well-becoming; that’s the crux of the book.

As I think through the Whole Life Practices, I have to say that Awe and Wonder wasn’t what I was expecting. It wasn’t what I automatically think of in this work. You shared that Brain and Body was where you learned the most, but I’m wondering if there was a moment of surprise for you in the process of writing about something that you heard or learned that really was an awe-striking moment for you or caught you off guard and really made you pause and think?

The first thing that was really transformational was that I decided (and you know this because you were working with me while I was doing some of this) to practice the practices myself. And to actually roadshow and test them and figure out where they were alive in my own life and where they weren’t – in the middle of writing the book. There are two practices, one is Build Community and Belonging and the other is Embrace Identities and Cultures. I took my family to Hawaii for the first time – and we’re native Hawaiian – and it was the first time in my life where I was going for work. I was with my mom. I was with my husband. I was with my children. And so all of my identities were all lit up – who I am as a spouse, who I am as a daughter, who I am as a mother, but also who I am vocationally and who I am as a native Hawaiian woman. And it tapped into a level of thriving, of well–being, of coming alive, of loving my life, that I didn’t even realize was missing.

A really transformational part of the writing of the book and the living of the book was realizing that when we walk through life if one of these 10 practices the lights aren’t on, we may not even realize the degree to which that’s diminishing the quality of life. And that’s true for kids if they are walking through their entire childhood and their culture and identity is not embraced in school. They may not know any different. But when that light comes on and you see the richness of that experience, you’re confronted with how much better life could be if all the lights were on. And so I think that was a really important one.

And the other thing that I’ll just say quickly – it’s a really small one – is that I’ve always known about the fight or flight when you know trauma and something scary – fight, flight, and freeze. But I learned while writing the book that there’s actually a second thing which is called “tend and befriend”. It tells us why at an evolutionary, ancient level of biological wiring, why relationships matter so much. Because our most primitive selves, in order to stay alive, we needed each other. It was safer to be in relationship with people. Having that most ancient part of evidence to know relationship and human connection is as fundamental to who we are and how we stay alive and how we stay healthy and well as the nervous system of our body being regulated in an emergency situation. And that was a pretty powerful small learning that clarified a lot of what I knew, which was relationships matter more than just about anything else.

My last question for you: I want to end our interview where your book begins. You worked with and selected a very special preface author. And I’m wondering if you can tell us a little bit about that preface author and why it was so important for you that the books start in that way.

Well, that author just happens to be right next to me. So let me do a little cameo appearance. (Justice came in and sat with his mom during this portion of the interview).

So I had Justice write the preface because in my first book I had really high-profile icons, including Karen Pittman, write the opening. And that was really important to set the stage. I wanted somebody who was kind of a highest in the field in terms of young people and then somebody who was the highest in the field in terms of the workforce and the future of work.

This is a book about kids, and so I wanted a kid to start it. But I wanted a child who was going to keep me honest. And I knew that Justice would write an honest opening to what it means to be a kid right now and the kinds of adults who really do see the whole of who he is.

It was a wonderful perk, but there was no persuasion or manipulation when he said, “Please just listen to my mom.” But the thing that he was able to say was I actually live this, believe it in like the deepest core of my core, and that I was really wanting to share it.

What do you think in terms of the power of you writing a preface for all of these adults who are opening up the book to read it?

I think it’s good to show what is actually happening, because a lot of adults don’t actually realize what us kids are going through. And they don’t all – I don’t want to say care – but they don’t really pay attention to it. And it’s just helpful, from a kid’s perspective, to just like see what they observe or see how they see the world.

Harrison, Justice’s younger brother has also been involved. He helped inform the preface and I’ve been including the boys in book signings because, ultimately, I wanted people to recognize symbolically and literally what they read first – that at the center of this book are the kids who are in our care. And this is a kid who is in my care, and this is what he has to say. And this is why we do the work.

Right? What do you think about the book?

I think it’s amazing. The fact that you wrote this much in 9 months, on weekends, in the basement is crazy.

Anything else you want to add in our last few minutes?

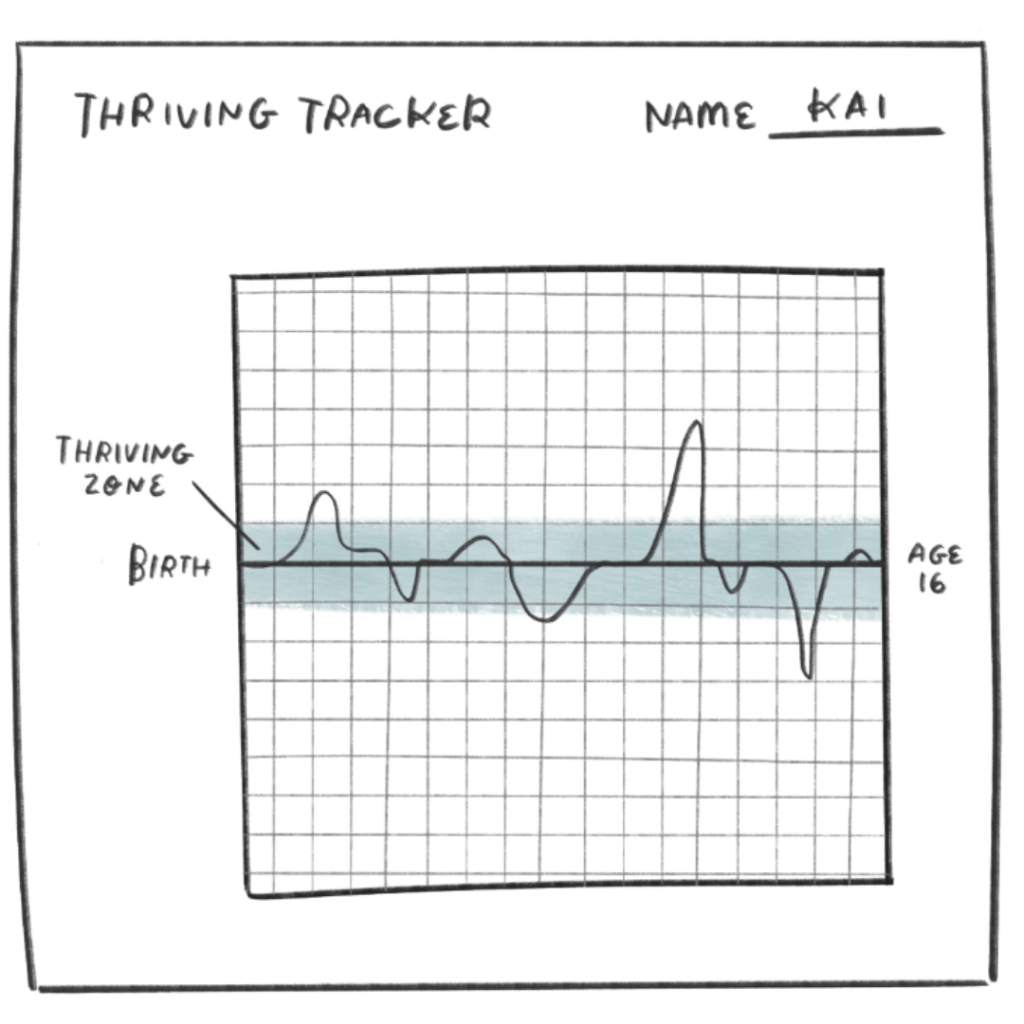

There is one other lesson that I learned in writing the book that was a real evolution. And that was that I used to think you shifted out of survival mode into thriving. Then you have these seasons of thriving. And what I actually learned – and there’s a picture in the very last chapter of the book, I call it a thriving tracker – is that in the course of a day, a kid actually goes up and down and up and down.

And this was really important for me because our kids are growing up in such hard times. It actually gave me so much hope because it showed that young people can thrive in moments and situations and settings, no matter what else. We can create the conditions that protect their childhood and prevent hardship for that hour, or for that class, or for that day. And that then our job is to expand and extend the situations in which that can happen.

This is not a book about systems change, which I’m involved in professionally. We have to do systems change. This is about the direct relationship and interactions that we have kids in a world that is broken and hard. And can it still be possible for them to grow and flourish and be okay?

Knowing about that thriving tracker was so important because it’s about how we create the conditions in their life where they’re just in the green zone, the thriving zone, more often than not. And if they dip down – because they’re struggling with their mental health or because they’re struggling with a particular adult or it’s just a rough day – they can go back up and you don’t have to wait a long time. So in a pandemic, or in a mental health crisis, or in a divorce, or in a hard school year, there are still ways we can create so many moments where they can experience thriving. And that felt very, very hopeful for me.

Hope is the word that I was just going to use. Thank you for leaving on such a note of hope.

More resources are available for community book clubs, educator and youth worker professional development. This immensely readable and accessible resource is extensively footnoted and informed by interviews with more than 50 scholars and champions of kids and can be used as a reference guide.

In addition to reflection questions and tools and tips built into the book, check out additional resources on WholeChildWholeLife.com, including discussion guides for professionals and for parents and caregivers.

All images and graphics used in this post were retrieved from the companion website for Whole Child, Whole Life: 10 Ways to Help Kids Live, Learn, and Thrive by Stephanie Mali Krauss. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, www.corwin.com. Copyright © 2023 by Corwin Press, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction authorized for educational use by educators, local school sites, and/or noncommercial or nonprofit entities that have purchased the book

No comment yet, add your voice below!