“For the past few years, schools have wondered what more they can do to meet the outsized emotional needs of their students. In many places, the answer appears to be interventions designed to be universal builders of emotional skills and comfort, often known as social and emotional learning.

“But social-emotional learning, or SEL, is not designed to address (diagnose or treat) mental illness, though it may create conditions for noticing and concern. What it can do is play an important role in promoting stronger human development and more responsive school environments.”

Associated Press reporter Jocelyn Gecker looks at examples of basic teacher training to spot warning signs of mental distress, offer constructive supports and implement protocols for reporting concerns and, looking beyond the classroom, documents the huge need for school health professionals. Gecker notes that an aptly named “Youth Mental Health First Aid” training program operated by the National Council for Mental Wellbeing is available in every state. California lawmakers are pressing for legislation to require that middle and high schools train at least 75% of their personnel in behavioral health through programs like this.

And in the CDC’s press release on its new survey data, Kathleen Ethier, Director of the CDC’s Division of Adolescent and School Health, offers a single message to schools wanting to do more to increase youth well-being and appropriately address mental health issues — Increase school connectedness:

“School connectedness is a key to addressing youth adversities at all times — especially during times of severe disruption. Students need our support now more than ever, whether by making sure that their schools are inclusive and safe or by providing opportunities to engage in their communities and be mentored by supportive adults.”

Ethier takes this recommendation further in an NPR interview, citing powerful longitudinal data on the correlation between not feeling connected in school and overall mental health:

“Young people who feel connected to others at their school…anywhere in 7th to 12th grade, 20 years later have better outcomes in terms of their mental health, in terms of substance abuse, in terms of experience and perpetuation of violence and in terms of sexual health.”

She recommends three simple, school-wide strategies for increasing connectedness, focusing, in this case, on LGBTQ youth, the highest risk group in the new survey:

1) Address the obvious things that isolate students (e.g. bullying) and emphasize the less obvious, but equally important issue of classroom management. Get the balance right to provide teens with structure while giving them the opportunity to feel heard and empowered.

2) Support connections to youth development programs that connect youth to community, build relationships and foster a sense of service.

3) Implement policies, practices and programs that support LGBTQ youth.

Ethier deftly dodges the interviewer’s question about whether recent state legislators actions to limit expression of gender and identity in schools are making the situation worse. But she makes a powerful closing statement, referencing again the heightened concern for specific marginalized groups:

“Something about protecting the most vulnerable youth means that the school is better for everyone; everyone improves…When you make schools more toxic for any student, you make them more toxic for all students.”

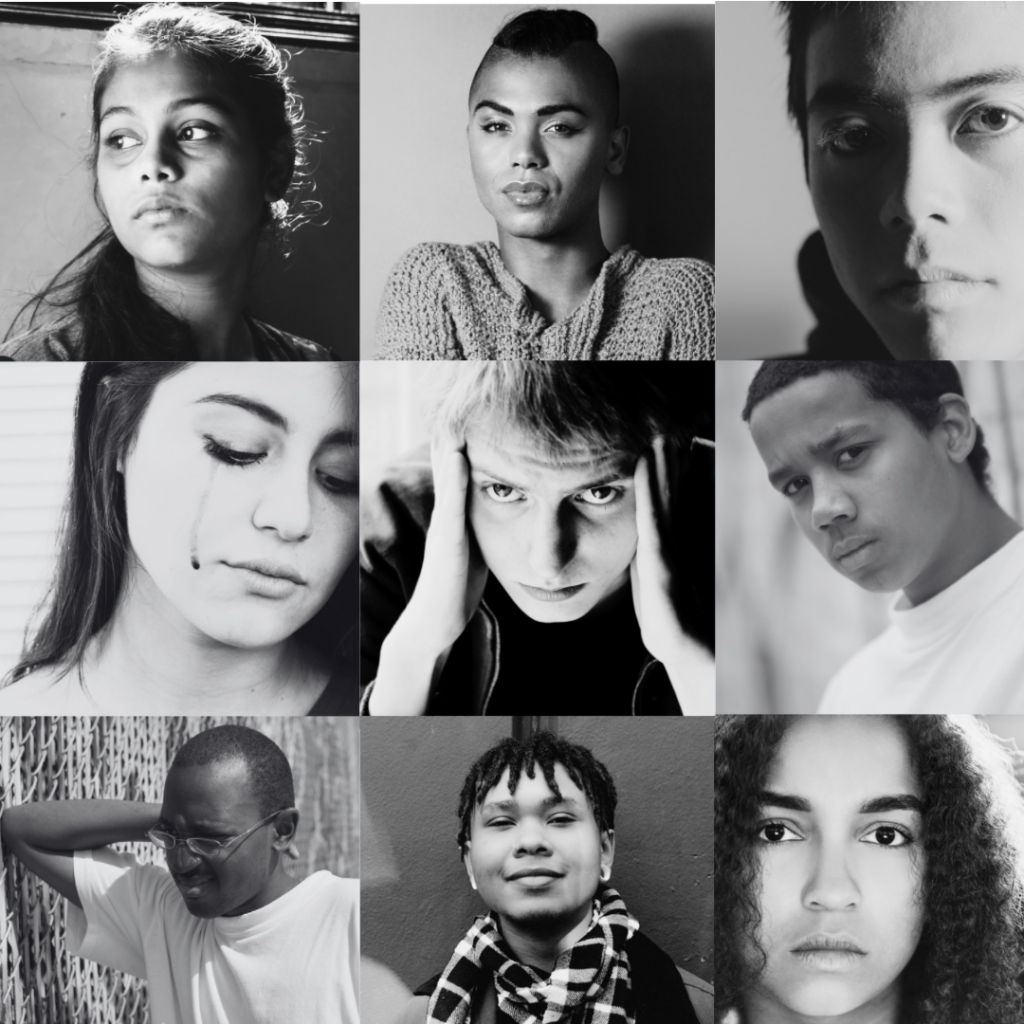

Amen to that. Any environment that is unwelcoming to specific groups of youth is a problem. But recent pressure to make schools “disappear” Black, brown, transgender or gay students is a crisis because if forces students to pre-empt their futures by leaving school, denying their reality, or, in the case of 47% of LGBTQ teens, considering ending their lives.

How can making any student group choose from these bad options be good for the whole?

No comment yet, add your voice below!