Last week was a heady and heavy writing week for me. I helped get an academic research piece I’m co-authoring to the finish line, reviewed several pieces written by others, wrote two commentary pieces, and gave written responses to interview questions. All totaled about 50,000 words all linked to two concepts – thriving and equity.

Last night, I got out of the house and went to the celebratory dinner for the first cohort of DC-XQ high schools – seven public high schools in Washington D.C. that are using the youth-centered principles and participatory processes developed by the XQ Institute to transform the learning experiences for their students. I had no role other than to clap for the school, youth, and community leaders whose proposals I read two months ago. Thriving and equity were the central concepts conveyed in each school’s description of their bold new mission.

I left the event determined to shorten the conceptual distance between the academic research paper (with 30 pages of references) and the seven action plans for high school transformation. Doing so will certainly help me sleep better at night. But I think it has greater importance. We need research-based, shared definitions in order to understand the different pathways individuals take and examine the power of equity-infused transformative approaches to learning and development.

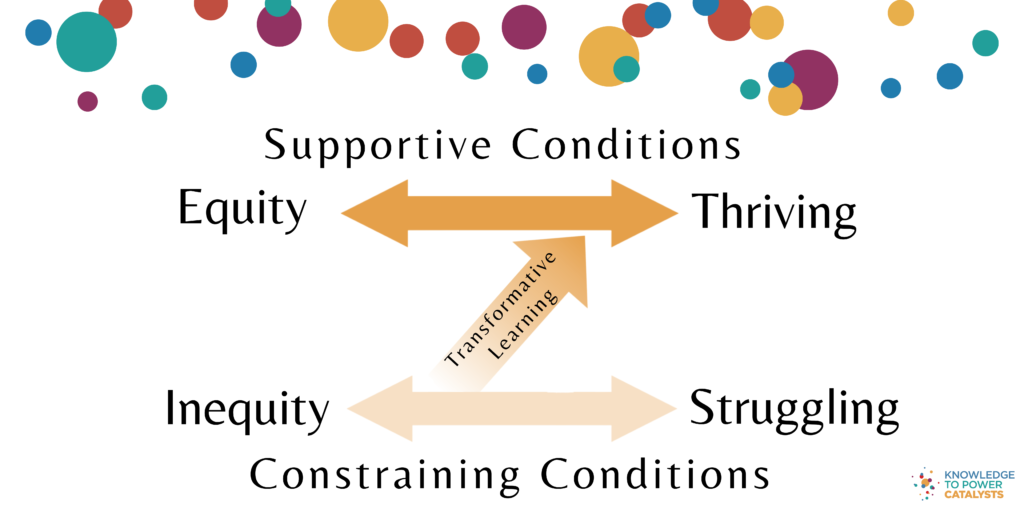

The basic premise of the paper is both simple and profound:

Thriving and equity are inextricably and dynamically linked to each other and to the conditions that support them.

The directional relationship between equity and individual thriving is straightforward and intuitive. Sustained or acute limitations on access to supports and opportunities do not make it impossible for individuals to thrive, but they do make it more difficult. Inequity not only effects the well-being, identity, and agency of the individuals in a group. It effects the group’s ability to uplift its individual members.

The directional relationship between thriving and equity, however, is less intuitive. Understanding this relationship requires acknowledgement of the fact that thriving is individual and collective. Other things being equal, the ability of a group to have a common sense of purpose, connectedness, and identity, affects the well-being of its individual members. “A rising tide lifts all boats.” Challenging and inequitable physical and material conditions can be offset by community cohesion.

But it is the dynamic relationship between thriving, equity, and the conditions that support them both that is the most important, especially for healthy youth development. Young people’s ability to thrive is not only dependent upon them having equitable opportunities. It is equally dependent upon their ability to understand and address challenging conditions and underlying inequities that affect them as a part of a group, community, or culture.

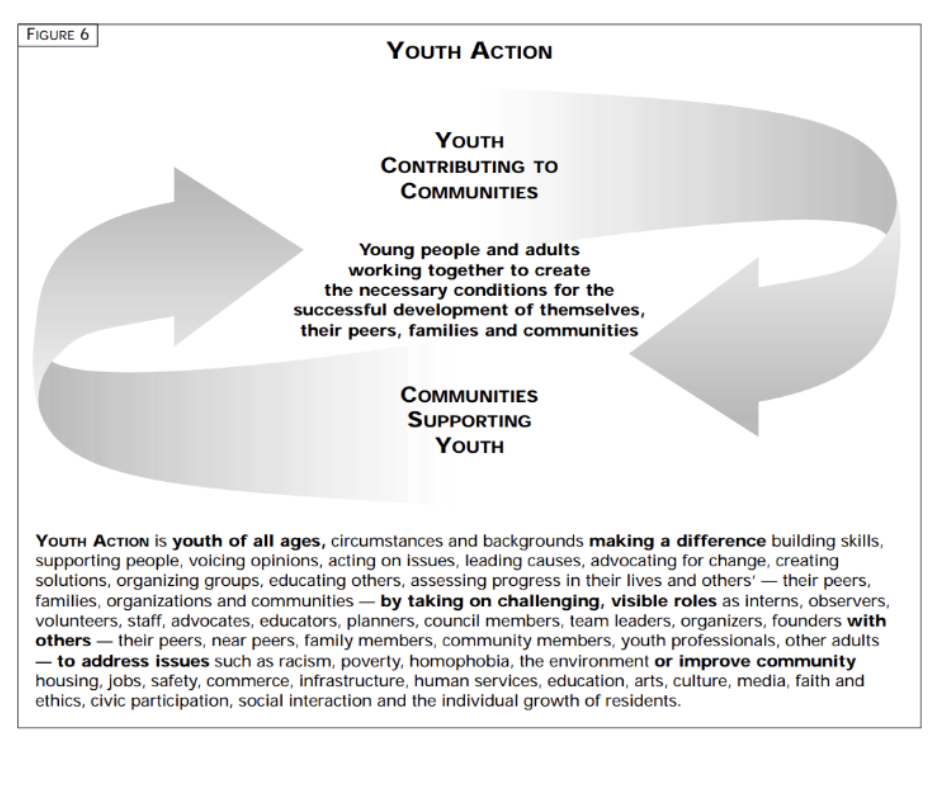

Youth contribute to communities. Communities support youth.

Twenty years ago, Merita Irby, Thaddeus Ferber and I used this simple double arrow graphic to explain the dynamic intersection between youth development, youth action, and community development. I like it because it centers young people as solutions to (not just beneficiaries of) community efforts to address inequities. But the graphic may not be explicit enough at a time when concerns about youth thriving and institutionalized inequity are in headlines almost daily.

It may be time for a set of three arrows that centers young people as agents of change.

Societal commitments to individual learning and development can be used to acclimate populations to constrained conditions, but commitments to transformative learning experiences that emphasize meaning-making, identity, competency, development, and agency can be used to accelerate thriving and equity while engaging youth to actively address underlying constraining conditions.

What visual works best for you to characterize how we can center youth experiences in our efforts to maximize individual and collective thriving and equity?

2 Comments

30 years ago, we referred to the child welfare example you shared as the “fix then develop” fallacy. And we offered examples of the harm caused from the other side. When young people and families that appear to be “doing well” can’t find or face stigma finding services they need (e.g., LGBTQ youth).

Love it! And I think being explicit about the conditions – both supportive and constraining – is helpful on this. The old visual I turn to from this paper quite a bit is the simple prevention donut. And where is the one about access to services that shows the service array – from crisis intervention to leadership development – along one axis, and low to high risk youth along the other? I’ve been thinking about the parallels to child welfare, where families who are considered to be at high risk of system involvement get emergency “prevention” services focused on safety, parenting and basic needs, while families with more resources have access to the broad range of experiences and settings that would fundamentally help all families thrive.