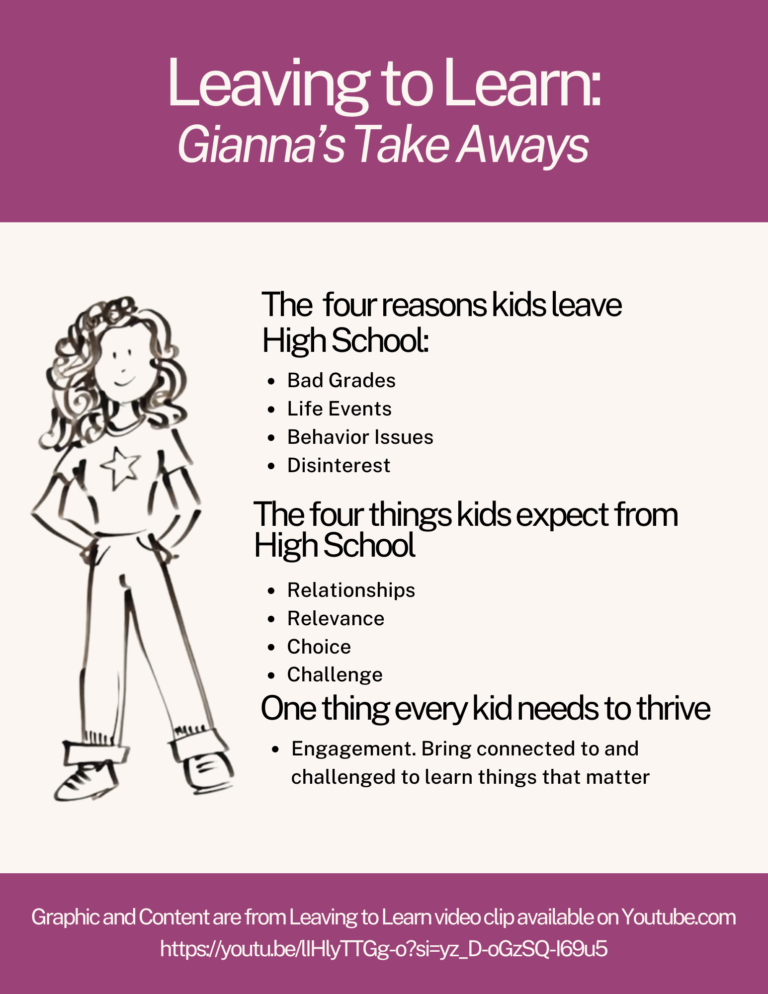

A month ago, we kicked off our first Centering Youth Thriving convening with Leaving to Learn, a 4-minute student narrated, animated video. Gianna makes a compelling case for why the best way to keep students in school is to let them leave school to have authentic learning experiences that matter to them with people in their community who are skilled and passionate about their work.

The video was made in 2013 to introduce the book Leaving to Learn: How Out-of-School Learning Increases Student Engagement and Reduces Dropout Rates. Author Elliot Washor is co-founder of Big Picture Learning, one of the oldest and largest networks of high schools that put students at the center of their own learning. I know Elliot. I’ve visited the Met, the original Big Picture school in Providence. I know the tremendous amount of work advisors do to ensure that their students are getting the foundational knowledge and skills they need while also monitoring their experiences in the community projects they choose. Leaving to learn sounded like a clever way to talk about open-walled schools.

A week later, we played the video for a group of National Education Association leaders who come together several times a year to explore issues relevant to their members. We’d been invited to spend an afternoon with them exploring the ideas in Too Essential to Fail. We thought the video would be an engaging way to elevate the converging expectations about schooling we detailed using surveys from the public, parents, teachers, youth workers, employers, and, of course, young people. It definitely struck a chord. But not in the way we expected.

Becky Pringle, NEA’s President, took issue with the phrase, suggesting that leaving to learn is absolutely the wrong message to convey in this volatile political climate. But for her and the majority of educators in the room, their concern was with more than the phrase. It was with the underlying implication that we should give up on teachers being able to deliver engaging, powerful learning experiences.

Leadership group members spent a good ten minutes affirming that teachers want to create this kind of learning in their classrooms. They shared stories of how their efforts to be creative in the classroom or help their students connect with the world outside of their classroom are thwarted by the system.

For them, the data shared in our report from a 2021 Learning Heroes survey that found parents and teachers agree that out-of-school time programs are important for elementary and middle school students because they better meet the expectations Gianna laid out in her video, was proof that parents, teachers, and out-of-school educators should be working together, not pulling apart.

Last year, Washor published Learning To Leave, the sequel to the 2013 book. The first book focused on the concept of leaving traditional classrooms to engage in real-world learning. The sequel “explains the principles behind and the reasons for generating New Ways of doing things which provide the basis for New Forms and the New Measures that facilitate, recognize, and credit learning that happens in and out of school.” It’s chocked full of student success stories and practical guidance for educators and policy makers.

There is no corresponding video yet for Learning to Leave, but this phrase, for me, conveys a more appropriate message. Learning to leave is a developmental goal that starts in infancy and continues through young adulthood. Helping a child or adolescent learn to leave starts with them believing they have a solid home base to return to. That adults know and have vetted the places they are going and believe that they have the knowledge and skills needed to be on their own. And, most importantly, that when the unexpected happens, as it inevitably does, that they have adults who can help them reflect, adjust and advance.

No comment yet, add your voice below!