“Public education is the most important investment America makes in its future, a tangible expression of our values and aspirations for society. Schools profoundly influence how students understand themselves, the roles and responsibilities they are expected to fulfill, and the country they will collectively create. A vision for public education is an essential touchstone for aligning strategies and actions to purpose and mission.”

This quote is the opening paragraph of “We Are What We Teach,” a nine-page call to action and vision statement from the Aspen Institute’s Education & Society Program. It is well worth the read. The team doesn’t pull punches. They cite two crises, a crisis of belonging and a crisis of opportunity, as two of the most important reasons we need a new vision of public education. They propose three succinct, balanced purposes for public education that highlight the outdatedness of the current standards, assessments, and accountability framework: Developing a sense of self, preparing for American democracy and civic life, and preparing for the world of work.

They acknowledge the need to be more explicit about the role of education in relation to other policies, investments, and social structures and to clarify education’s role relative to other important factors that influence life outcomes. They appropriately note the expanded roles schools took on during the pandemic to lead on public health, technology infrastructure, and the provision of safety-net services. Their conclusion: “This level of primary responsibility is unsustainable over the long-term and needs to be right-sized relative to the essential roles of other agencies and partners.”

They acknowledge the need to be more explicit about the role of education in relation to other policies, investments, and social structures and to clarify education’s role relative to other important factors that influence life outcomes. They appropriately note the expanded roles schools took on during the pandemic to lead on public health, technology infrastructure, and the provision of safety-net services. Their conclusion: “This level of primary responsibility is unsustainable over the long-term and needs to be right-sized relative to the essential roles of other agencies and partners.”

I agree. But I am not just concerned about the unsustainability associated with schools taking on public health and basic services roles. I am equally concerned about the unsustainability associated with schools not sharing responsibility for ensuring the types of educational experiences that develop a strong, integrated sense of self and draw learners into their roles as citizens and workers. The agencies and partners essential for the first goal are different from those who contribute to the second.

During the pandemic, the National League of Cities proposed a “community learning hubs” model to help city leaders understand the range of services, supports and opportunities young people need and the range of places they might receive them beyond schools. They argued that communities that collaborate, align programs and resources, and center their work in equity will be better positioned to bounce back from the pandemic and see longer-term education, health, and economic gains.

The National League of Cities report proposed that the community learning hubs model has five benefits that can help right-size the role of schools while also increasing efficiency and equity:

• Collect data to determine neighborhood-specific needs

• Leverage local facilities, staff expertise and community resources

• Prioritize health and safety concerns

• Address systemic inequities

• Provide comprehensive wraparound supports

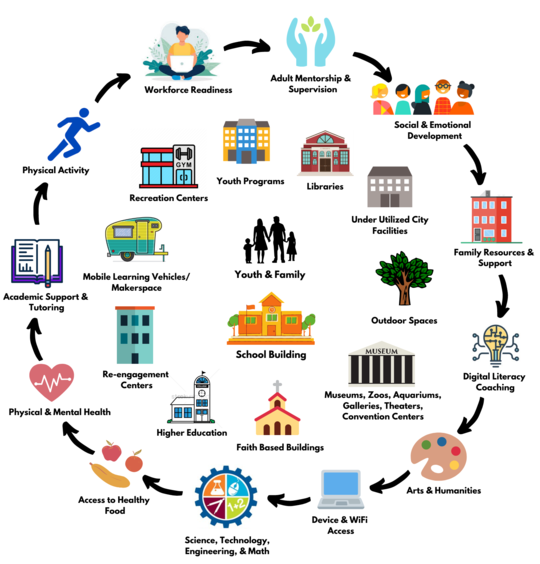

NLC’s diagram, however, suggests a broader, bolder goal: community-centered learning and development:

The outer ring of icons depicts includes more than the health, technology, and support services that stretched schools to thin during the pandemic. The ring includes arts and humanities, STEM, physical activity and adult mentors. It represents the full range of services, supports and opportunities young people need to be productive, healthy and connected. It includes the basic services some learners need without deemphasizing the supports and opportunities all need.

The inner ring of icons depicts the physical places where these services, supports and opportunities could be delivered. Health clinics, food pantries and social service agencies are important for ensuring equitable access to learning opportunities. But they are not included in the model because they are not primary places in the community where learning happens.

The inner ring of icons depicts the physical places where these services, supports and opportunities could be delivered. Health clinics, food pantries and social service agencies are important for ensuring equitable access to learning opportunities. But they are not included in the model because they are not primary places in the community where learning happens.

The school building and families are at the center of the visual because these are the places formally charged with ensuring that each and every learner builds the competencies, confidence and connections they need to be ready to participate fully in family, work and civic life. Many schools naturally integrate the outer ring functions into the day to ensure that the core academic content is not only rigorous, but relevant, well-received and authentically utilized. None, however, are as important as what the XQ Institute calls proficiency in functional literacies and foundational knowledge.

Executed too forcefully or separately from core instruction, even functions like social and emotional development and mentoring can be perceived as undermining the mission of schools given their sole responsibility for academic teaching and learning. So how can we help schools right-sizing from the pandemic look for opportunities to assess and adjust their roles in providing all of these functions? Four quick suggestions:

• Assume that every function is seen as the primary responsibility of at least one other institution.

• Assume that families relate to these other institutions as much as, or even more than, they relate to schools.

• Assume that the other places connect with each other as much as, or even more than, they connect to schools.

• Reflect on the new connections that flourished, albeit unevenly, when school buildings closed at the beginning of the pandemic. Assess how they could be nurtured or why they weren’t continued.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development recently issued a report outlining four scenarios for the future of learning:

• Schooling extended (continued reliance on academic certificates from accredited institutions)

• Education outsourced (diverse forms of private and community-based alternatives to schooling)

• Schools as learning hubs (schools retain most functions, but competency recognition drives ecosystem development, leveraging resources from other institutions)

• Learn-as-you-go (digitalized, AI driven learning that allows knowledge, skills and attitudes to be assessed and certified directly).

All four are possible. As I see it, however, only the learning hubs model has the potential to be not only efficient, but also effective and equitable.

No comment yet, add your voice below!